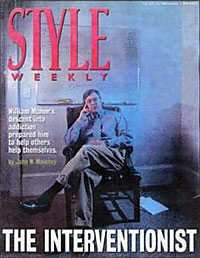

The Interventionist

by John W. Maloney, Style Magazine, Richmond, VA, 1996

NOTE: This article was written in 1996. Today, we use several different models of intervention, many of which were not described in this article.

It was June 10, 1994 and he was decidedly hung over. The night before, he had run up a tab he couldn’t cover at Buddy’s until a friend spotted him the cash to escape. Looking rough and feeling bloated, bad even for a Saturday morning, he accepted a ride with a family friend to what was supposed to be a job interview with an influential lawyer.

At least he remembered that he had to go somewhere.

These were strange days for him. Twice through treatment and twice fallen from the wagon, he knew the dean was revoking his law school diploma for unfinished class work. He hadn’t started studying for the bar exam. He was neither a student nor a lawyer, just an alcoholic and his family knew he was drinking even more than before.

Having never spent a day in his life in a public school, he was an accomplished son of affluent parents. Friends said he was brilliant and self-destructive in the same breath. He dated rich girls who partied hard and if a legal career emerged, then he would have fooled ’em all.

Status, women, and alcoholism, to boot.

But he was essentially trapped most days in his West End rental in mid-1994, paralyzed by debt, swimming in guilt.

Every day, a new sack of empty beer bottles accumulated next to the dirty armchair where he was supposed to be studying. He never counted the bottles, but they made for a heavy bag.

If he went out to drink, he typically closed the place.

A job prospect at this stage – though it was inexplicable that anyone would really want to hire him – was worth showing up for. The interview, however, was a ruse. Stepping through the doorway at 2405 W. Main Street, he encountered his parents, grandparents, an uncle, an aunt, a brother, and two sisters inside, as well a stranger named Bill Maher who knew him better than he could ever imagine. Here in this nondescript little building without a sign, his life would change, perhaps forever.

This was an intervention. The family had had enough. He took a seat.

“I’m thinking I’ll never stop drinking. They’re so full of shit,'” he recalls. The meeting began. Carefully tendered family testimonials unfolded around him. His father cried.

As each person took a turn telling him how his disease had affected them, “the biggest heartache of my life” set in. “I felt like I had gotten out of the shower and was sitting there naked in the chair.”

By the end of a “seamless” intervention, he agreed to try therapy again. He’s going on three years of sobriety, and stays active in the recovery community in the West End.

Bill Maher, he says, is masterful at staging interventions—both for what happens and what doesn’t happen. Sitting to the side, sometimes he doesn’t say a word during the actual intervention because the family is prepared and the “identified patient” is willing to go along. Maher’s business is saving people from their addictions one hairy family crisis at a time. He estimates that he has conducted more than 400 interventions (Update note—by the end of 2003 he has conducted more than 1600).

The Family Intervention Center of Virginia Inc. is a simple one-room office in Richmond, Virginia with high-backed leather chairs, an erasable drawing board on the wall and a desk where Maher piles case folders around a computer and a cordless phone.

He does his work on his feet, talking and listening.

The phone rings. It’s a distraught mother whose thirty something son is drinking himself to death out west. He’s undergone detoxification twice. She still sends him money.

“You’re not going to like this, but you might as well fly out, go to the liquor store, buy what he drinks, go to his place, take out a glass and put in some ice and pour him a drink,” Maher says into the phone, his words laced with authority, albeit the understanding, sympathetic variety.

Maher is silent as the conversation pauses for the mother to cry.

After listening for a few more minutes, and explaining the bare basics of the intervention process, Maher says she’s going to have to hire him to go any further. The cost is flexible, ranging as high as $3,000 plus expenses. For out-of-town clients, it’s a three- or four-day process. For local clients the process can span a month, with six or more sessions, at $100 an hour.

The mother on the phone will probably hire him the next time she calls, Maher says, clicking off the phone. Her son is dying and she has to save him.

At 44, Maher’ s eyes look tired but he explains his purpose with determination. He’s relaxed in jeans, a sweater and running shoes. His war stories as an alcoholic come out in small pieces, fragments of a harrowing picture he infers is best described in summary, not detail. He isn’t the type to impress listeners with his dramatic exploits, but he shares enough for people to know he was in the gutter once. The man some of Richmond’s highest-standing families are baring everything to was someone altogether different 15 years ago.

He hustled people. He had a gun pointed against his head. He stole what he couldn’t buy.

Why he didn’t die along the way is a mystery. He claims divine providence. Raised in an upper middle class Ohio family, he was scarfing his old man’s Valium as a kid, drinking a six-pack a night at 17. Most of his 20s are a blur, he says. In a combat battalion of the US Marines, he had access to prescriptive drugs and used all he wanted. In 1983, after some seven years back in the civilian ranks, he was sucking down a fifth of liquor, a case of beer and “all the drugs I could get my hands on” in a given day, he says.

Week-long binges, holed up in cheap hotels with four or five half-gallons, were normal. Maher says that at his worst he was transporting his belongings in a kettle grill on the streets of Upper Marlboro, Md.

“I literally was on my knees puking and drinking Smirnoff 160 [proof] at a commode at the same time,” he says. (If images of Nicholas Cage in the movie “Leaving Las Vegas” come to mind, you’re not far off, Maher adds.)

“What happened to me was the booze turned on me—my liver stopped functioning,” and unfiltered alcohol flooded his bloodstream in all of its toxic mayhem. For the first time in his life, Maher was a fall-down drunk. From there, the only direction was up. He started to pray.

“I’m alive and the only things I know a lot about are death and alcoholism,” he says, having shared all he is going to tell about himself.

In a cruel curriculum spanning decades of drink and drugs, Maher’s descent into addiction hell gave him the tools to help others halt their way down.

He lives in a world of absolutes: Alcoholism is a disease. It is progressive and fatal. Family and friends can help a patient recover—but they have to change their outlook.

In the summer of 1994 she was 45, a mother of one, relatively friendless and drinking approximately a liter of wine a day after work and on weekends. It took about that much wine to guarantee that when her head hit the pillow at night, she would fall deep into sleep and escape what haunted her.

“I couldn’t stand to be near my husband,” she says over coffee at the Starbucks in Willow Lawn. She’s now something of a new-age spiritualist; life for her now is an extended renaissance. She has a dinner group with other women like her, the sort of gathering where they never discuss tethering themselves to more thoughtless men.

Disarmingly comfortable, in describing her own trials and tribulations, she typifies the Type-A recovery advocate celebrating her own recovery, and eager to share the 12-step message to anybody who wants to hear it.

There are meetings every night, in every part of town. The little booklet in her handbag lists every one.

As an 18-year-old in Boston, she was raped at gunpoint, an experience she has accepted as the random woman on the other side of the random door her random rapist happened to knock on.

At peak consumption, she says, she was buying wine by the jug at Price Club each week. Tipped off by her husband, her psychiatrist raised the issue of drinking to her in 1994. She was becoming like her mother, an alcoholic. Determined that she could defy the charge she took just five drinks in five weeks.

Angry and furious, she says she became a “dry drunk,” someone whose addiction is temporarily starved. Mobilized by denial, she felt she had taken charge of this newly exposed vulnerability.

“I knew I had a problem when we planned a party for our child at Chuck E. Cheese’s and I started looking forward to it because I knew I could have wine with dinner” and no one would question her, she says.

Her last drink was on July 3, 1994: a vodka tonic. On July 6, she met Bill Maher in the usual way—by complete surprise. (Note: Today, an Intervention Model that doesn’t “surprise” the addicted individual is available. See more about the invitational intervention model in the intervention section of this website)

Summoned to a late afternoon meeting at her job to discuss a business matter, she entered the intervention completely unaware. When she saw her parents, she says the first thought this was some kind of surprise award ceremony. They were supposed to be in California. In the presence of her husband, sister, parents and her work supervisor, she accepted Maher’s offer to sit down. He was the calming influence in the middle of the emotional storm.

One by one, each person read prepared statements about her drinking problem. “I was very, very angry,” she says. “I hadn’t been drinking for weeks,” but they continued “bringing the charges.”

She knew she had to go to treatment. She also vowed to divorce her husband when she came back. (She did.) Life would have to start over without him.

“Bill was brilliant. Work was the one place I felt safe—they pulled that mat right out from under me,” she says.

On the arm of her alcoholic sister who was already in recovery, she exited the building through the back. Her bags were packed. Last year at her 30th high school reunion at a prestigious northern boarding school, she was voted “most changed.”

“There is a love in me that I didn’t know could exist,” she says. “We talk a lot about surrender. I had to open up.

“I never realized how sick I was until I started getting well.”

Maher drags a red marker from the top left corner of his office drawing board to the bottom right comer. This is the first leg of the alcoholic’s three-legged journey, he says. When the significant people in the alcoholic’s life arrive at Maher’s office—the intervention team—he immediately focuses their attention on the disease and not the person; they will be ganging up on the alcoholism or the substance addiction, not their friend.

They have to believe, he implores, that the crisis isn’t some behavioral flaw, that no mythical amount of will power will thwart the urge to drink, smoke, snort or shoot up.

“Alcoholism is the only disease that tells you that you don’t have a disease,” Maher says, repeating some of the buzz-phrases that capture his clients’ attention. The downward progression can take months, years or decades, and it is fatal. “There are doctors, dentists and lawyers out there with idiot IQ’s,” from alcohol-related memory deficits. And the “psychological maneuvers” an alcoholic can exhibit in supporting his denial can be mystifying. “We are masters at compartmentalizing our lives,” Maher says. Fittingly, by bringing together the people who occupy the vital compartments of an alcoholic’s life spouses, siblings, parents, employers, ministers, friends the intervention creates a “bottom” from which the person can recover.

Maher’s professorial lecture unfolds with “The Three Stages of Alcoholism.” In most cases, the identified “patient” is well into or beyond the middle stage. In a tireless recitation from a pad of notes, Maher launches into his stand-up gig.

Stage one begins with denial and sincere delusion. Then there’s preoccupation with booze or drugs, and increased tolerance from chasing the high; guilt moves in quickly as the person realizes he needs five or six beers when everyone else has two.

Maher’s writing moves downward along the line.

The “identified patient” uses more than he intended, then conceals or lies to hide his guilt; switches to pot, or wine or substitutes something else. Other interests, such as hobbies or clubs, fall off and he settles for less in his life, from relationships to work.

Bizarre things are happening now at the start of the second stage. Maher is quickly filling his second board now and typically, the intervention team is beginning to see where the identified patient is going. Their experiences with that person are showing up on the line, too.

There are DUI’s, money problems, blackouts or grayouts that can last weeks at a time. Conceptual reasoning begins to fall off and promises to quit fail. The alcoholic discovers the value of the morning drink to take the edge off the night before. He makes long, rambling calls, or “telephonitis,” as Maher calls it. Family and friends are avoided as he drinks with inferiors people he wouldn’t normally associate with.

He neglects nutrition, looks sluggish. Paranoia becomes apparent. Self-pity becomes extravagant. Anything is a reason to drink now. Shame is emerging and he knows that he is an alcoholic.

The diagonal line for the third phase begins with sleep disorders. Suicide crosses his mind. Anxiety disorders prompt twitching, cramping and other gastrointestinal disorders. The body takes protein from muscle tissues to offset nutritional deprivation. Tremors start. There are sexual impairments. The heart is weakened and the immune system grows depressed. Fear, guilt and helplessness are masked by aggressiveness. Then, written at the bottom comer of the drawing board: “death.”

After three full boards about alcoholism, the intervention team’s arrival at death somehow comes suddenly, despite several hours of discussion.

People who have followed Maher’s “stages” lecture say it changes the way they look at alcoholics forever. The educational process is draining. Hours pass without ever taking an eye off that drawing board. Some team members will complain.

Ideally, in local cases Maher will meet with the intervention team four times before the actual intervention. Participants are asked to abstain from drinking and drug use during these weeks and several hours are reserved before the event for rehearsal.

In the end, the “identified person” is asked to go to treatment. If he refuses, the team insists; and if he still refuses, they are prepared to tell him the consequences of continued addiction. A wife might predict divorce; a boss foresees termination; a doctor expects serious health problems; children threaten to leave.

Asked to meet with the family of a friend on drugs earlier this year, he arrived at Maher’s office with a simple question: How could this interventionist know what’s right for somebody he’s never met?

Maher says the friend was a standard skeptic, perhaps a little more adamant than some.

“We all wanted him to get help,” but not through some kind of trendy experiment, he says. “I said, “I ain’t buying the fact that you can stand at the blackboard and diagnose my friend.” Sensing the tension in the first meeting, he thought: Is this process going to get the family at each other’s throats? Opposed to going any further, he sought advice from a psychiatrist, who said doctors diagnose patients all the time from the information on the chart. As the family rehearsed, he played the role of the identified patient, channeling his own feelings into being the encircled individual; he challenged the others, preparing them for the worst. “It became a very loving, caring process and I sensed relief for the guy in the middle,” he says.

When an alcoholic’s “compartments” are brought together in the same room, and Maher has brought together as many as 15 people in a patient’s life into his office for a team intervention, “the iceberg syndrome” occurs, her says. Skeletons fall out of the closets. The group share experiences, most sad, some just ugly, others horrible, even despicable.

Maher has heard em’ all.

The West End man who leaves his three small children in his Suburban idling outside the crack house, where an equally addicted friend notices it – and tells the team. A husband announces to his stunned wife that they are driving into a rough area so he can score some cocaine, which she didn’t even know he was using. When she walked into Maher’s office, her face was badly bruised from the beating she and her man received when a gang pulled them both out of the car – and she tells the team. A wife reveals her agony at being sodomized by her husband – always when he’s on cocaine – and she tells the team. A brother did cocaine with the addict. A friend shared a hooker with him. The pre-intervention sessions can be chaotic events unless the interventionist sticks to the common objective of getting the person to treatment. Maher says bluntly that sessions never get out of control. “This can be the most intimate moment a family has ever had,” Maher say.

The new model for interventions is very different from the kidnappings that highlighted the original technique. The intervention team isn’t there to dump on the patient, Maher says. When an intervention team begins to assemble, Maher selects one member each week to call the patient and explain why he or she is meeting with a specialist on alcohol or drug addiction, shifting the issue to the team. Carefully coached, the team members individually inform the patient that the disease of addiction is hurting them as friends, family or employers, and that they want to address the problem. After a few weeks, the team is prepared for the intervention and the patient knows the most important people in his life are meeting together about how the disease is impacting them. Each of them has told him/her they are willing to confront the disease. Finally, he/she is invited to an intervention workshop – not duped into coming like the old method prescribed.

The best aspect of the new model, Maher says, is that the patient usually doesn’t arrive at the expensive treatment facility angry at having been ambushed or “kidnapped.” The new way sends people to treatment in a mindset to try to get well the day they arrive. Giving the patient more time to dedicate to “retooling” with the appropriate skills to tackle the disease so they can embrace life.

Maher says he’s had patients barge into his office before an intervention, sit down, tell him who they are and demand that he stop interfering with their families. In the most polite way possible, Maher says he doesn’t work for the patient, he works for the people who love him. The alcoholic can’t fire him. Usually, the fee has been paid in advance.

In executive interventions, Maher works for the addicted person’s company. The fee is $7,500.00; many companies are more than willing to pay that much to get valuable personnel into treatment. Maher explains what the employee is going through. He also facilitates the workplace confrontation – it’s always at the workplace – always with the CEO. A letter, with documented proof of the addiction’s impact on the workplace, is prepared. The letter offers a choice: treatment at the company’s expense (a car is waiting) or instant termination. Maher is there to counsel the addict if he chooses treatment. Maher can only remember one case when treatment was refused.

As families come and go from his office, he sees bottomed-out patients off to treatment; then he usually sees them again after that, at a mall, at the movies, or just around town. And usually, he says, the patients look well – and that, Maher says, is a humbling, sometimes emotional reward.

Reprinted with permission.

NOTE: This article was written in 1996. Today, we use several different models of intervention, many of which were not described in this article. See more about intervention.